Through discussions with colleagues, clients, experts on the needs behind ‘Diversity, Equity Inclusion’ and by developing DE&I projects and exploring the varied voices on the topic, it emerges how the language, the choice of words is delicate: minimal dictionaries, extensive introductions and premises. It is like walking on eggshells. Why?

words have a history: diversity and inclusion

‘The limits of my language constitute the limits of my world,’ said Wittgensteing.

Words are dense, they speak of our culture and are the result of layers of meaning accumulated over time, one on top of the other, like matryoshkas. To question words is to question our comfort zone. However, it is important to open the matryoshkas of the main words related to ‘inclusion’, to become aware of the culture that created them and to choose suitable words. This act is not aesthetic or formal, but helps us bring out the cultural lenses through which we filter and translate what happens to us.

Words create worlds, shape our thoughts that then give rise, externally, to processes and decisions. These have a strong impact on the organisational and non-organisational contexts we live in.

Even inwardly, when we do not speak, ideas, feelings and thoughts take the form of an ‘internal dialogue’.

The term Diversity & Inclusion, or Diversity Management originated in the 1980s in the United States out of a need in society and business[1]. The people targeted by these programmes have often pointed out how the choice of these words is not appropriate and leads to processes and decisions that are not always optimal.

Against Inclusion is the title Fabrizio Acanfora gives to the introduction of his volume Oltre le parole. Dizionario minimo di diversità.

Going beyond the provocative title, we read:

‘I do not think that inclusion is an equal process. Because it involves a majority holding the power to decide who can be a full member of society and who cannot. People arbitrarily assigned to so-called minorities do not receive equal rights at birth, but those rights are granted to them by the group that at a given moment in history proclaims itself the majority, and which is privileged with those rights.’[2]

If we open up the matryoshka of this word, we discover that the term inclusion comes from the Latin includere, formed from in and clàudere, to close, and means ‘to close in’.

In mathematics, inclusion is the relationship between two sets, whereby one of them contains the other as a subset.

words create worlds: uniqueness rather than diversity

Something similar happens when we delve into the word diversity, as we saw in the previous article[3], in the name of which we create, with the best of intentions, programmes and pathways in organisations.

‘If we are not able to define diversity as an autonomous concept and not necessarily as the opposite of normality, we will not succeed in freeing it from social stigma. Inclusion will always remain a process that starts from normality – perceived as the right thing – and invests a diversity that is all in all passive, eager to join the club of healthy, normal people, of those who are not singled out as defective or strange […] A diversity dependent on the idea of a normality that, paradoxically, is non-existent in nature’.[4].

What is needed on the subject of ‘diversity and inclusion’ is a small revolution, like the one that has been initiated in recent years in the design of products or services, placing the person, with his or her experiences and needs, at the centre. The more people can be fully themselves within organisations, the more effective listening, understanding and service will be to the external recipients of products or services. By ‘fully ourselves’, I mean fully responsible for our personal development, capable of questioning our deep-seated beliefs, of building processes and cultures that facilitate this mutual adaptation and evolution. Where the context is still hierarchical, this step is the necessary starting point for those at the top, so that the empowerment of cultural and organisational evolution is real.

For all these reasons, we prefer to speak of Oneness, Equity and Wholeness (UE&I), rather than DE&I, although the wording remains the same in this transitional phase to facilitate the bridging necessary for mutual understanding.

pic by Belina Fewing | Unsplash

DE&I is not an island: it must be integrated into organisational processes

These initial reflections reveal how DE&i/DEIB Diversity Management programmes demand to be integrated into the employee experience, starting from listening to and understanding the needs of the people they are intended for.

Programmes dedicated to these topics need to be an integral part of organisational transformation projects, leadership development, process re-design and need courage, awareness and appropriate language.

I believe that an effective way to approach these issues is to value the uniqueness rather than the diversity of people’s contributions. This means creating a culture and an organisational structure that enable the full expression of people, rather than focusing on symbolic decisions of inclusion. The implication is to ask ourselves what new values and behaviours we need to develop to support the requirements that such a culture demands. We cannot take these steps without changing anything.

Is there a way of describing our organisations and describing ourselves that is not ‘by difference’, comparative, ‘categorical’, but one that rather tells of uniqueness?

Let’s take an example: think of the word ‘dis-ability – different ability’. This still implies that there is a ‘normal ability’ and a ‘different’ one. Our culture rests on a language that constructs the narrative on the greater or lesser divergence from a norm. In the case of neuro-divergence, Gitnux[1] tells us that 15-20% of the population manifests some form of it, developed due to genetic or environmental factors.

Our description of neuro-divergence to date is ‘diagnostic’ and creates a stigma around these people. This has a strong impact on their participation in the world of work (these people are 3-8 times more likely to be unemployed than people ‘without disabilities’, with an unemployment rate of between 30 and 40 %).

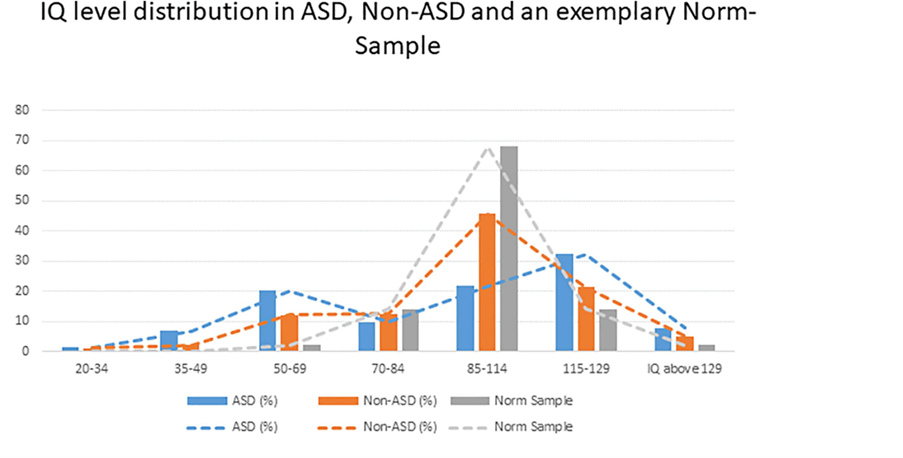

Such a narrative tends to overlook the fact that most of these people have special mathematical, pattern recognition and memory skills, and a different statistical distribution of IQs, with them being much more represented in the higher IQs at 115 [2].

It is also well documented that neurodiverse teams can be up to 30% more productive than other teams.

from de&i to ue&i: hints for organisation in everyday life

What can change in our thinking and the resulting organisational choices if we replace the perspective of UNICITY with that of ‘diversity’?

If we stop thinking of differences as a divergence from a gold standard andwe start describing them as a characteristic expressing the variety, richness, exceptionality of the members of a work group, of the employees of a company, what can happen?

- For instance, the recruitment process can evolve from a purely culture-fit approach to one also based on culture-add.

- The feedback process can evolve towards an authentic exchange that looks towards common goals rather than towards the confirmation of a standard linked to perceptual bias.

- The design of career paths can evolve from a purely meritocratic vision towards an equal opportunities vision, which questions how I design positions and not just who is best to fill them.

- This in turn opens up essential questions about the concept of talent itself: is it acquired or innate? Can it be transferred or is it context-bound?

- Finally, the organisation of spaces can evolve. Generally, a good impact metric is that an ‘inclusive’ design is better for everyone and not just for a circumscribed category.

Certainly, work is needed to rethink language, processes and decision-making models. But the question is: what is the cost of not taking these steps?

if you want to continue this conversation, WRITE TO ME, LET’S TALK ABOUT IT!

Discover the previous article! 👉 The biographical approach to understand DEI&B topics

note

[1] Diversity management came to life in the late 1980s in the United States, a ‘multicoloured’ country par excellence, in order to value workers from different cultures, races, religions and backgrounds. Indeed, it was in this country that companies began to approach the problem of how to motivate and coordinate such a diverse workforce. And how to value, attract and retain the best talents belonging to such heterogeneous groups. As a result of the obvious changes in the workforces of large American companies, there is a need for people management systems that are as diverse as possible. In order for them to succeed in the arduous task of employing diversity in a strategic manner. Gianluca Longo, Diversity Management and Work-Life Balance, Master’s thesis.

[2] Acanfora p. 19

[3] The term diversity, in Latin dīversĭtās, derives from the verbs dīvertĕre and dēvertĕre composed of vertĕre (to turn) and dis (elsewhere). They indicate turning somewhere else, but also moving away, deviating, changing direction.

The adjective dīversus and the noun dīversum derived from it indicate a quality and mode of being that refers to an idea of separation. Of contrariety and distance.

In this sense, dīvertium (divorce), a derivative of the same verb, expresses even more, and with greater semantic intensity, this sense of splitting and contrast.

[4] Acanfora, p.94

[1] https://gitnux.org/neurodiversity-in-society-statistics/#:~:text=The%20number%20of%20patients%20with,both%20genetic%20and%20environmental%20factors.

[2] https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.856084/full