A few weeks ago I finished the last season of Masterchef, a program of a competition between amateur chefs which I was passionate about, and not a little, I must admit!

Every Thursday evening, after having put the children to bed, I watched it with my partner.

I was looking at it – a professional distortion – also from a management point of view; I have to say that it gave me some very interesting keys to understanding the theme of teamwork.

In what sense? Let’s first take a look at how Masterchef works.

The game is a competition between aspiring chefs, judged by 3 judges on a series of tests: the mystery box, the invention test, the outdoor test and finally the pressure test.

It is an individual competition, all against all, where the most talented and sometimes lucky one wins. Being set up this way, the best talents emerge as the episodes progress, while the worst ones are eliminated. However, there is a time when these 15-20 aspiring chefs also have to play as a team in order to win, during the outdoor test. The goal of this test is to prepare the best menu in a short amount of time. A leader is designated for each of the two teams, who is in charge of choosing the various team members and guiding them through the test. Then the actual competition begins.

Authoritative leaders, non-authoritative leaders, team members in destructive conflict, team members aligned to the common goal: the dynamics you see are very much typical of the functioning (or dis-functioning) teams we tell our clients about. And this is where my interest sparked.

That calls for a little parenthesis first.

What we’re trying to do every day at Peoplerise is to work the way marketing works with the customer world. This approach consists of using analytical insights to guide our choices in the world of people management, working less on “trust” and “guruship” that are typical of the HR world, and more on actions supported by data. The innovative people management model of Google is an example of this: http://t.co/bnQ55je0kC .

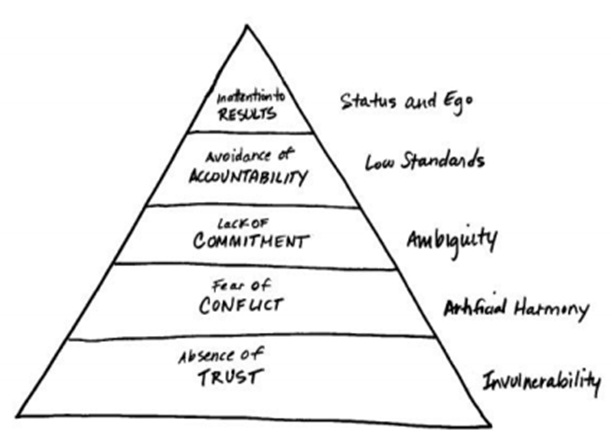

Among all the areas of study that we have collected and that we are working on, there is one that is really difficult to measure precisely: the value that teamwork gives to the last line of the profit and loss statement. Lencioni himself, our methodological reference in working with teams, tells us how teamwork is the real sustainable competitive advantage for companies, yet highlights the fact that it is not clearly measurable: its added value must therefore be accepted, almost ideologically. Teamwork means mutual trust, the ability to deal with conflict, the desire to engage and take responsibility for achieving common goals (see figure 1).

Fig.1: Lencioni,P.,2011, The five dysfunctions of a team: A leadership fable, Jossey Bass

As a result of this desire to empirically measure the contribution of teamwork to the final result, I found an excellent guinea pig in Masterchef, not so much to make a precise statistical study, but to watch carefully and critically the results of teamwork in a simple and immediate game. And the results were not exactly what I expected. But back to Masterchef.

The two teams begin to compete (and they will do this with different set-ups 6 times during the program). I begin to observe the dynamics of the two teams: where the 5 dysfunctions of teams are applied and where they are not. I am disappointed: in the first two outdoor tests the link between a team that works well and success is not so clear: the team that wins is not the one that works best. I instinctively begin to think that perhaps teamwork as we think of it is not the ingredient for success.

Third outdoor test: the aspiring chefs are getting fewer and better. And suddenly the trend changes: the team with the best teamwork wins! And so it goes also in the fourth, fifth and sixth outdoor test. Teamwork made the difference, even on teams where there was less talent.

So what’s the deal with these two different situations? Why didn’t teamwork make a difference in the beginning? Then a light bulb lit up for me. There is a situation where teamwork may not be the primary competitive advantage: it may be useful yes, but not fundamental, not distinctive. That is, when the competition is at a lower level. If I want to compete at low levels, then having one or two talents on the team can allow me to win challenges. But when the competition rises to high levels, when the weakest chef is still quite talented, having one or two more talented chefs than the others is no longer enough. You have to work well as a team to win the challenge.

Think about our world today: hyper-competition on a global scale and a war for talent. That’s why teamwork really has become a key lever of success: it makes the difference between the good and the very good, where mediocre is no longer allowed. What do you think? And in your own realities, how does teamwork work?